- ShreeHistory

- History

- Hits: 63

- ShreeHistory

- History

- Hits: 63

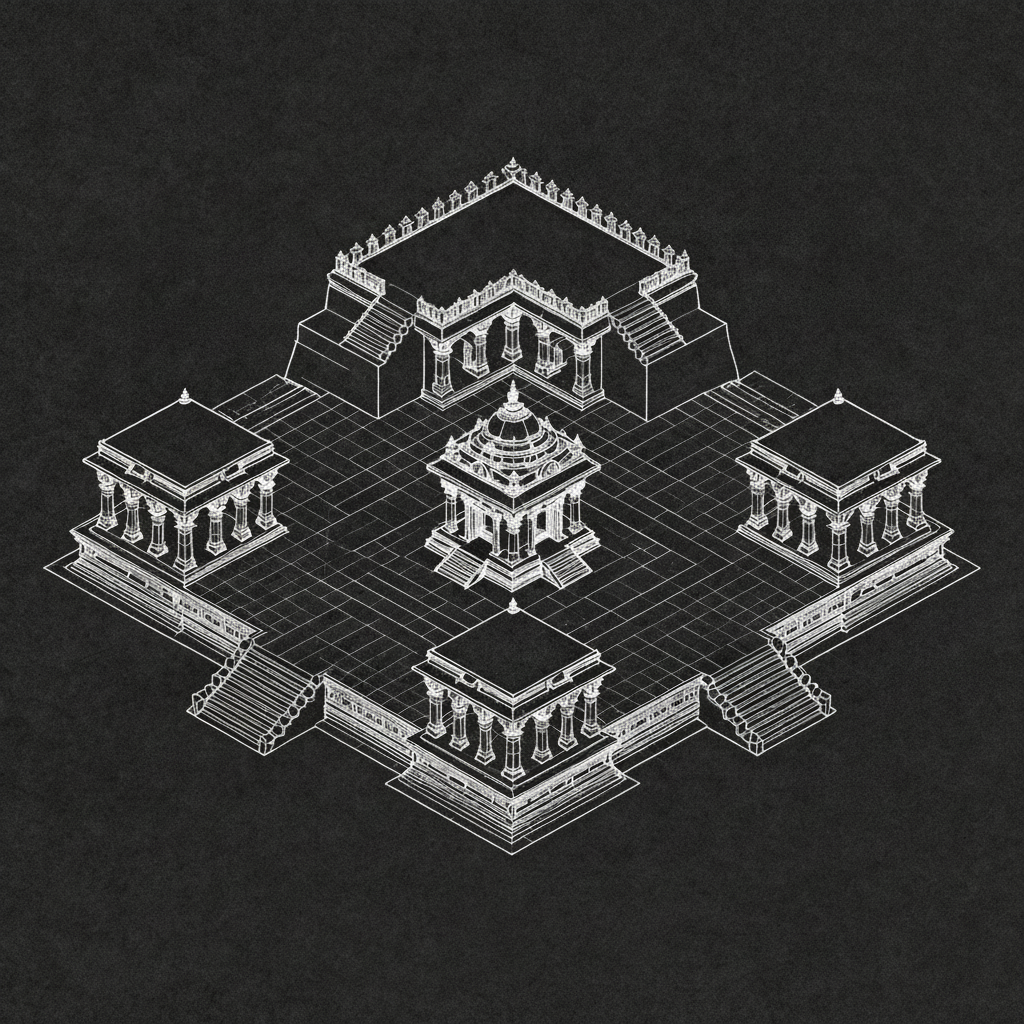

The Sarvatobhadra temple represents one of the most sophisticated planning systems in ancient Hindu architecture, and its principles became the fundamental blueprint for major monuments built during the Mughal period in India, particularly Humayun's Tomb and the Taj Mahal. This architectural connection reveals the deep indigenous roots underlying structures commonly attributed solely to Islamic architectural traditions

The Sarvatobhadra temple, described in detail in the Vishnudharmottara Purana (an ancient Hindu text on architecture), belonged to the eighth classification of Hindu sacred structures. The name derives from sarvata (from every side) and bhadra (auspicious), indicating a temple characterized by auspiciousness and accessibility from all directions.

The Sarvatobhadra temple exhibits distinctive elements that make it unique among Hindu architectural forms:

1. Elevated Square Platform (Jagati)

The temple rests on a broad, square terrace called jagati—a raised platform that serves multiple purposes including circumambulation (pradakshina) and establishing sacred space. This elevation creates both practical and symbolic separation from the mundane world.

2. Central Sanctum (Garbha-griha)

At the heart of the plan sits the square garbha-griha (literally "womb-house"), the innermost sanctum housing the primary deity. This represents the cosmic center, the axis mundi connecting heaven and earth.

3. Four Mandapas in Cardinal Directions

Surrounding the central sanctum are four mandapas (pavilions or halls) extending in the four cardinal directions—north, south, east, and west. This creates a cruciform or cross-shaped plan radiating from the center.

4. Four Corner Chambers (Prasadas)

Between the four mandapas, in the diagonal corners, sit four smaller chambers or subsidiary shrines (prasadas). This arrangement creates what R. Nath describes as an "octagonalized-square plan" when the corners are chamfered.

5. Four-Way Accessibility

The Sarvatobhadra features entrances at all four cardinal points, allowing approach from any direction. Staircases on each of the four sides of the platform provide access.

6. Enclosing Rampart (Prakara)

A surrounding wall or prakara defines the sacred precinct, with subsidiary shrines (devakadis) positioned at the corners of the terrace.

7. Sacred Water Features

Integrated into the design are beautiful tanks and water channels arranged around the central shrine on the terrace, serving both ritual and aesthetic purposes.

8. Panch-Ratna Symbolism

The temple embodied the panch-ratna (five-jewel) formula: one central shikhara (tower) over the garbha-griha and four subsidiary shikharas over the four mandapas, creating a cluster of five towers with the central one dominating.

Multiple ancient Hindu architectural texts describe the Sarvatobhadra:

Vishnudharmottara Purana provides the most elaborate description in its 87th chapter of the third part, devoting an entire chapter to this unique temple type

Matsya Purana (Chapter 269) specifies that Sarvatobhadra temples should bear many shikharas

Brhat-Samhita prescribes four doors, many domes, many beautiful chandrashala (moon-shaped arch forms), five storeys, and a breadth of twenty-six cubits

Visvakarmaprakasha and Samarangana-Sutradhar also document this temple form with variations in measurements and proportions

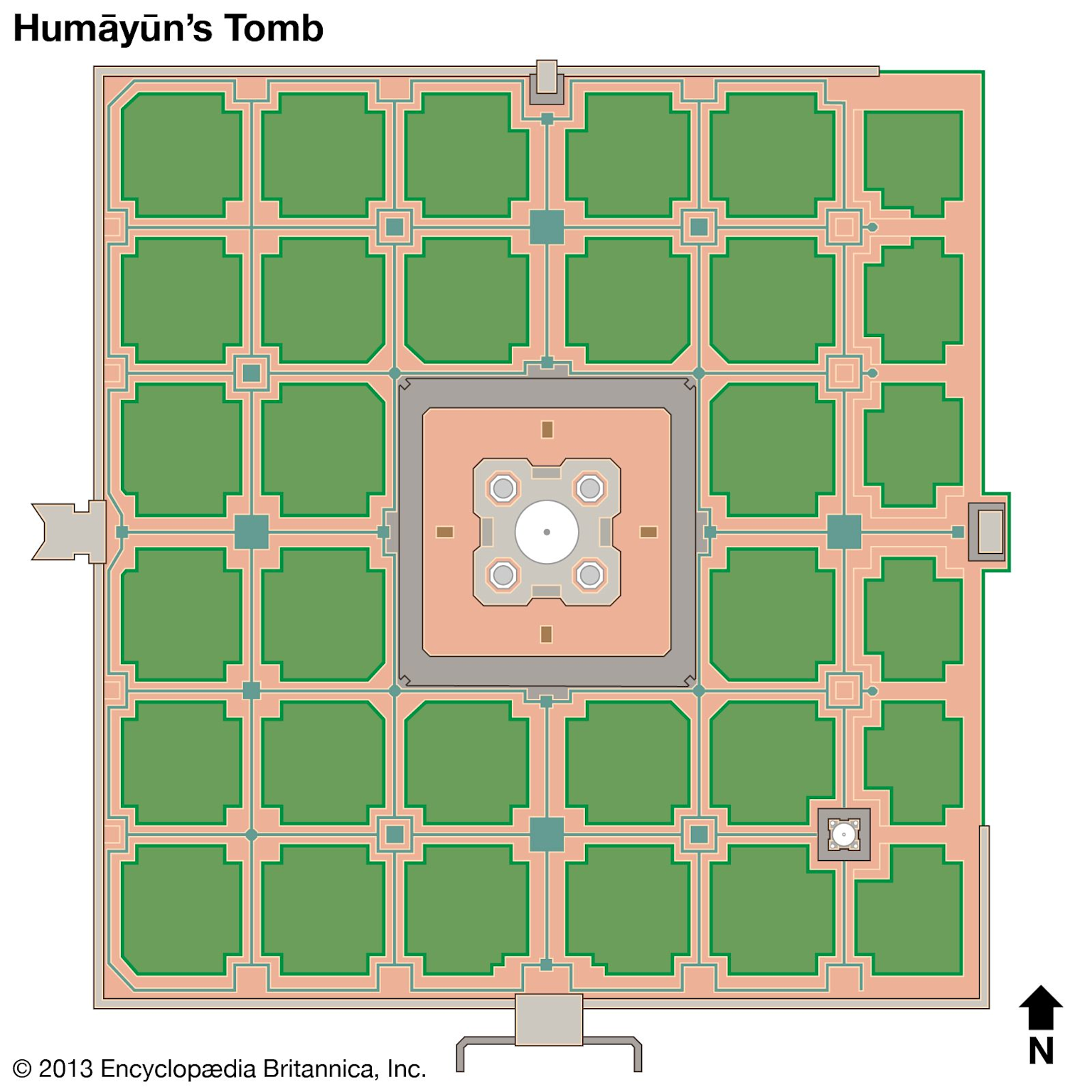

When Humayun's Tomb was constructed between 1564-1570 in Delhi, the structural correspondence to the ancient Sarvatobhadra temple plan became unmistakable. R. Nath, in his doctoral dissertation "The Immortal Taj Mahal," makes this connection explicit.

Plan Configuration: The Octagonalized Square

The tomb sits on a raised plinth 22 feet (6.71 meters) high, directly paralleling the elevated jagati of Hindu temples. The main structure follows a square plan measuring 156 feet (47.54 meters) per side, with its angles chamfered (cut at an angle), thus creating an octagonalized square—precisely the Sarvatobhadra configuration.

R. Nath explicitly states: "This description fundamentally corresponds to the plan of the tomb of Humayun and as there is no such prototype traceable in Persia or any other Islamic country". This unequivocal scholarly acknowledgment establishes that the planning system derives from indigenous Hindu architectural traditions, not from Persian or Islamic sources.

Interior Arrangement: Garbha-griha and Surrounding Chambers

The interior spatial organization replicates the Sarvatobhadra system with remarkable precision:

Central octagonal chamber: Functions as the garbha-griha, the focal point of the entire structure

Four octagonal corner chambers: Correspond to the four corner prasadas of the temple plan

Four side rooms: Represent the four cardinal mandapas

Interconnecting passages: All spaces connect through corridors, creating the circumambulatory (pradakshina) path characteristic of Hindu temples

R. Nath further identifies this arrangement with the Hemakuta temple system, which featured an Andhakarika (dark ambulatory)—a circumambulatory passage surrounding the central garbha-griha, enclosed within outer walls. He concludes: "This was known to the Indian builder and so the interior plan of the tomb probably owes its origin to him rather than to Mirak Mirza Ghiyas or any other Islamic builder".

Four-Way Accessibility: Cardinal Direction Gateways

Like the Sarvatobhadra temple, Humayun's tomb complex has gateways in all four cardinal directions. The main entrance on the west corresponds to Hindu temple orientation principles, which sometimes place primary entrances facing west for Shiva temples, as prescribed in the Shulba Sutras.

Each gateway provides axial approach to the central tomb, maintaining the four-fold symmetry inherent in the Sarvatobhadra concept. The pathways from each gateway lead directly to the central structure, preserving the Hindu principle of approaching the sacred center from multiple auspicious directions.

Water Features: Sacred Hydraulics

Small tanks and water channels integrate into the platform design, paralleling the sacred water features prescribed for Sarvatobhadra temples. The hydraulic system includes:

Overhead tanks ensuring water pressure

Underground earthen pipes feeding fountains

Channels (chadars) with flowing water

Lily ponds at intervals

Fountains marking cardinal and intercardinal points

This sophisticated water engineering reflects Hindu understanding of sacred hydraulics, where water represents purification, prosperity, and the flow of cosmic energy.

While Babur introduced the Persian char-bagh (four-part garden) concept to India, providing the landscape setting, the architectural plan of the tomb structure itself derives entirely from the Hindu Sarvatobhadra system.

R. Nath clarifies: "The square plan of the main structure, approachable from all the four sides, was however known to the Indian builder since ancient times". The indigenous architect adapted the ancient Sarvatobhadra plan to the new context of tomb construction, demonstrating continuity of Hindu architectural knowledge systems.

The char-bagh garden, divided into four quadrants by water channels, actually resonates with Hindu cosmological concepts of four-part spatial division found in vastu purusha mandala (the sacred geometric diagram underlying Hindu architecture). The four cardinal directions hold deep significance in Hindu thought, corresponding to directional deities (dik-palakas) and cosmic ordering principles.

In a sealed conference hall in Islamabad last year, a retired Pakistani general delivered a blunt message to a gathering of strategists. “Pakistan does not have a No First Use policy, and I’ll repeat that for emphasis. Pakistan does not have a No First Use policy,” declared Lt. Gen. Khalid Ahmed Kidwai, former head of the nation’s Strategic Plans Division. Across the border, India’s leaders publicly espouse the opposite stance – a doctrine pledging that India would not be the first to launch nuclear weapons. But behind these divergent nuclear postures lies a worrisome reality: both South Asian rivals are quietly expanding their atomic arsenals, refining their missiles, and straining a fragile deterrence with new ambiguities.

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amsmath, amssymb, geometry, xcolor}

\geometry{a4paper, margin=1in}

\title{Understanding \textbf{Varga} and \textbf{Nija} in Sanskrit Mathematics}

\author{Perplexity AI}

\date{\today}

\begin{document}

\maketitle

\section*{Introduction}

The terms \textbf{varga} (वर्ग) and \textbf{nija} (निज) are fundamental to interpreting classical Indian mathematical texts like Aryabhata’s \textit{Aryabhatiya}. Their meanings and contextual usage reveal critical insights into ancient mathematical methodologies.

\section{\textbf{Varga} (वर्ग): The Concept of "Square"}

\subsection{Literal Meaning}

\textbf{Varga} translates directly to "square" or "group" in Sanskrit. In mathematics, it specifically denotes:

\begin{itemize}

\item The \textbf{square} of a number (e.g., \textit{pañcavarga} = \(5^2 = 25\))

\item A \textbf{class} or \textbf{category} of numbers (e.g., odd/even \textit{varga})

\end{itemize}

\subsection{Mathematical Applications}

Aryabhata uses \textit{varga} extensively:

\begin{itemize}

\item \textbf{Square of a number}:

\textit{Yavad vargād vargaśodhanaṃ} ("Subtract the square from the square as much as possible") refers to algebraic operations involving squares.

\item \textbf{Area of a square}:

\textit{Vargaṃ caturasraṃ} ("A square is quadrilateral") implies \textit{varga} as a geometric square.

\item \textbf{Astronomical cycles}:

\textit{Varga} also denotes divisions of planetary orbital periods.

\end{itemize}

\subsection{Example from \textit{Aryabhatiya} (Verse 2.3)}

\begin{quote}

\textit{Vargādvargaṃ śuddhiḥ} \\

("The purification [result] from the square of squares")

\end{quote}

This likely refers to iterative squaring in astronomical calculations.

\section{\textbf{Nija} (निज): The Nuanced Meaning of "Own"}

\subsection{Literal Meaning}

\textbf{Nija} means "own," "inherent," or "intrinsic." It emphasizes a \textbf{self-contained property} of an object.

\subsection{Mathematical Context in \textit{Aryabhatiya}}

In the sphere volume formula:

\begin{quote}

\textit{तत्र निजमूले हतं घनगोलः फलं त्रिघ्नविशेषम्} \\

(\textit{tatra nijamūle hataṃ ghanagolaḥ phalaṃ trighnaviśeṣam})

\end{quote}

\subsection{Interpretation Challenges}

\begin{itemize}

\item Traditional translation: "multiplied by its own square root" \\

\( V = \pi r^2 \times \sqrt{\pi r^2} \approx 1.77\pi r^3 \)

\item Problem: Overestimates true volume (\( \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3 \)) by 33\%.

\end{itemize}

\subsection{Reinterpreting \textbf{Nija} as a Geometric Ratio}

Scholars argue \textit{nijamūle} may instead mean \textbf{"inherent base ratio"}:

\begin{align*}

\text{If } \textit{nijamūle} &= \frac{4}{3} \times r \text{ (radius):} \\

V &= \pi r^2 \times \frac{4}{3}r = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3

\end{align*}

\section*{Conclusion}

The term \textbf{nija} exemplifies how Sanskrit mathematical texts encode complex ideas through compact phrasing. Aryabhata’s formula, when decoded as \( \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3 \), reveals a sophisticated understanding of solid geometry that parallels Archimedes’ work.

\end{document}

Gingee Fort, located in present-day Tamil Nadu, was a formidable stronghold consisting of three citadels on separate hills. Its strategic location made it crucial for:

Controlling trade routes between the Deccan and South India

Providing a secure base for Maratha operations against Mughal forces

Maintaining links with southern kingdoms like Thanjavur and Madurai

After Sambhaji's execution in 1689, Rajaram Bhosale undertook a daring 18-month journey to Gingee:

Traveled 1,200 kilometers through hostile territory

Led by Khando Ballal and Santaji Ghorpade

Used disguises and diversionary tactics to evade Mughal patrols

Reached Gingee in November 1690

Rajaram declared Gingee the new Maratha capital:

Fortified defenses under engineer Govind Pant Bundela

Created supply networks with local Tamil chieftains

Appointed Santaji Ghorpade and Dhanaji Jadhav as mobile field commanders

Aurangzeb dispatched a massive army under Zulfiqar Khan:

100,000 troops including elite cavalry

Heavy artillery and siege equipment

Support from local Nawabs and chiefs

The defenders employed multiple tactics:

Three-tiered defense system:

Outer perimeter of mobile cavalry

Middle ring of fortified positions

Inner citadel strongholds

Supply Management:

Underground granaries stocked for years

Secret water channels and reservoirs

Hidden paths for reinforcements

Under Santaji Ghorpade and Dhanaji Jadhav:

Regular raids on Mughal supply lines

Night attacks on enemy camps

Coordination with forces in Maharashtra

Rajaram's wife Tarabai emerged as a key leader:

Organized intelligence networks

Managed diplomatic relations with southern kingdoms

Supervised fort logistics and morale

The siege proved costly for Aurangzeb:

Multiple commanders replaced due to failure

Massive expenditure on maintaining siege forces

Growing desertion rates among troops

In 1698, Rajaram executed a brilliant escape:

Used diversionary attacks by Santaji Ghorpade

Slipped through Mughal lines during monsoon

Returned to Maharashtra to lead resistance

The fort finally fell to Zulfiqar Khan in January 1698:

Most defenders had already evacuated

Minimal strategic gain for Mughals

Enormous resources wasted in 8-year siege

Depleted Mughal Resources:

Estimated 100 million rupees spent

Loss of experienced commanders

Demoralization of troops

Maratha Advantages:

Time gained for reorganization in Maharashtra

Proof of defensive capabilities

Enhanced prestige among southern powers

Weakened Mughal Authority:

Demonstrated limits of imperial power

Encouraged other rebellions

Strained treasury resources

Maratha Resurgence:

Established southern presence

Developed new military leaders

Built alliance networks

The siege influenced later warfare:

Emphasis on mobility over fixed defenses

Integration of local support networks

Importance of supply chain disruption

Remembered in Maratha history as:

Symbol of resistance against overwhelming odds

Example of strategic depth in warfare

Inspiration for later independence movements

Primary Sources:

Akhbarat-i-Darbar-i-Mualla

Chitnis Bakhar

Dutch East India Company records

Modern Studies:

"The Marathas 1600-1818" by Stewart Gordon

"Military System of the Marathas" by S.N. Sen

"The New Cambridge History of India: The Marathas 1600-1818"

The Siege of Gingee represents a crucial chapter in Maratha military history, demonstrating their ability to conduct complex defensive operations while maintaining offensive capabilities. It marked a turning point in the Mughal-Maratha conflict, proving that the Marathas could sustain resistance even when driven from their homeland.